I was completely blown away by Joe Hill’s book, NOS4A2. I have read some of his previous work – Horns and Heart-Shaped Box – but with his most recent book, Hill has definitely crafted a treasure. It’s all here in this book. It is tight and it is just a lovely little package of dark fantasy and horror wrapped up and waiting for you. You must go read this now.

I was completely blown away by Joe Hill’s book, NOS4A2. I have read some of his previous work – Horns and Heart-Shaped Box – but with his most recent book, Hill has definitely crafted a treasure. It’s all here in this book. It is tight and it is just a lovely little package of dark fantasy and horror wrapped up and waiting for you. You must go read this now.

The gist of the story is that Victoria (Vic) McQueen learns as a young girl that she can travel to wherever she needs to go via a bridge – the Shorter Way Bridge – that just kind of appears for her. The bridge is magical and conjured into reality by Vic when she concentrates on an object or place, and initially she can only conjure the bridge when she is on her Raleigh. She begins by using the bridge to help her find things that she is looking for – a lost bracelet, a misplaced picture, etc. One day, though, Vic goes out looking for trouble and finds it in Charlie Manx, who steals children and travels his own version of magic roads to a place he calls Christmasland. Vic escapes Manx when she is a child, but later, as an adult, she must find and confront him again in order to rescue her own child.

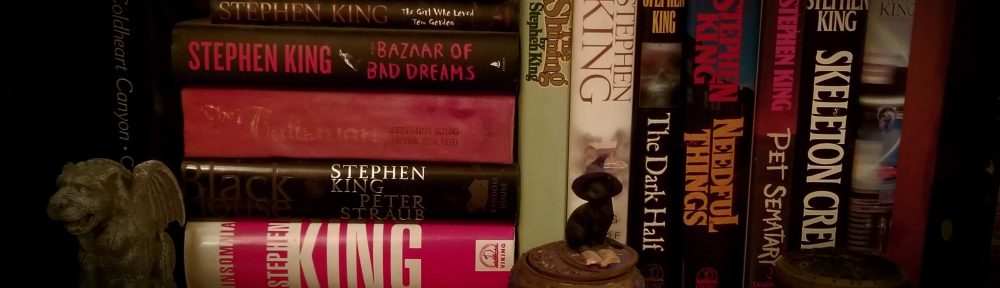

I liked that this book follows Vic from childhood to adulthood. I also like the character Hill has created – she is a real woman, and not a stereotype. I know several women like her and everything about her personality, skills, and history rings true. She has tattoos and knows how to use both a wrench and a pen. What I think I especially like about the book is how skillful Hill is at writing this woman. This is clearly written by a man who finds strong, eccentric women attractive and is not threatened by them. I found myself thinking about this a lot as I read. I am well aware that Joe Hill is the son of Stephen King, and while Hill has most definitely made his own name as a writer, I did find myself thinking about some of Stephen King’s work – especially Lisey’s Story, a book in which I felt King did a superior job of writing a real woman. Both of these men get it.

But, Hill definitely has his own style. I can feel my generation in his words. It’s something underlying the descriptions,

Vic squeezed the brake, let the Raleigh gently roll to a stop. It was even more dilapidated than she remembered, the whole structure canting to the right so it looked as if a strong wind could topple it into the Merrimack. The lopsided entrance was framed in tangles of ivy. She smelled bats. At the far end, she saw a faint smudge of light … The bridge waited for her to ride out across it. When she did, she knew that she would drop into nothing. She would forever be remembered as the stoned chick who rode her bike right off a cliff and broke her neck. The prospect didn’t frighten her. It would be the next-best thing to being kidnapped by some awful old man (the Wraith) and never heard from again.

the choice of characters,

Lou worked out of a garage he had opened with some cash given to him by his parents, and they lived in the trailer in back, two miles outside of Gunbarrel, a thousand miles from anything. Vic didn’t have a car and probably spent a hundred and sixty hours a week at home. The house smelled of piss-soaked diapers and engine parts, and the sink was always full. In retrospect Vic was only surprised she didn’t go crazy sooner. She was surprised that more young mothers didn’t lose it. When your tits had become canteens and the soundtrack of your life was hysterical tears and mad laughter, how could anyone expect you to remain sane?

the towns and locations. There is a rougher feeling that is smoothed out by the Christmas theme of the book and the magic that infuses the story, from the Shorter Way Bridge to Manx’s malicious car. While it feels much like something King would write, it’s not. It’s all Hill. And it’s all wonderful. I want to carry this book around with me and read it again. I love that there isn’t a neatly wrapped ending, and that the comments he provides in “A Note on the Type” are even less neat than the “official” ending. I think I’m a little in love with Joe Hill at this point, so it’s possible that I can’t really talk about this book coherently. Man. Joe Hill. I can’t wait for the next one!