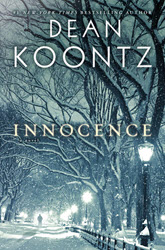

Innocence is Koontz’s most recent book, and I picked it up in the library not too long ago. I will be honest and say that I passed it by several times because the description on the jacket really doesn’t do it justice. However, after finally picking it up I was rewarded with one of those rare experiences of having a book that I just didn’t want to put down, that I thought about during the day, and which I looked forward to being able to sit back down with again at the end of the day.

Innocence is Koontz’s most recent book, and I picked it up in the library not too long ago. I will be honest and say that I passed it by several times because the description on the jacket really doesn’t do it justice. However, after finally picking it up I was rewarded with one of those rare experiences of having a book that I just didn’t want to put down, that I thought about during the day, and which I looked forward to being able to sit back down with again at the end of the day.

Addison Goodheart is a monster with a heart of gold. When people see him, they seem to find him so repulsive that they try to kill him. His own mother was not able to stomach him for longer than 8 years, and so he has lived most of his life deep under the ground in New York City, where he was fortunate to be found and rescued by another like himself. One night the beauty to this beast enters his life, but she, too, has some problems – a social phobia so strong that she has lived her life basically as a recluse. Together, these two take on a great evil, and the ending – well, it is a most interesting take on “happily ever after”.

Addison’s character is of a type that Koontz has been experimenting with for awhile. There are similarities between Odd Thomas (from the series of the same name), Christopher Snow (Fear Nothing), and Deucalion (from the Frankenstein series). All of these individuals have the characteristics of victims and those destined to be permanently outcast from society: they see ghosts, they are somehow monstrous, or they have a rare disease. However, they are all also fearless in their pursuit of justice for the innocent; they fight to protect those who are weaker than society. In short, these characters consistently display qualities of empathy.

Koontz’s writing in Innocence hooked me from the beginning:

Having escaped one fire, I expected another. I didn’t view with fright the flames to come. Fire was but light and heat. Throughout our lives, each of us needs warmth and seeks light. I couldn’t dread what I needed and sought. For me, being set afire was merely the expectation of an inevitable conclusion. This fair world, compounded of uncountable beauties and enchantments and graces, inspired in me one abiding fear, which was that I might live in it too long.

There is a graceful contrast in this book between the brutalities and beauties of life. That the grotesque can somehow become beautiful is the theme that we all remember from the fairy tale “Beauty and the Beast”. But in Koontz’s hands, this tale is both modernized and inverted. Both of these characters are beasts, but they are also beautiful. There is a reverence of life that plays throughout this story, a deep sensation of what has been taken from us all by society:

Disobedience brought time into the world, so that lives could thereafter be measured to an end. Then Cain murdered Abel, and there was yet another new thing in the world, the power to control others by threat and menace, the power to cut short their stories and rule by fear, whereupon death that was a grace and a welcoming into life without tears became no longer sacred in itself, but became the blunt weapon of crude men.

The way of peace and empathy is rewarded in this book, just as it is in many of Koontz’s other works, including those of Odd Thomas; however, it is a reward that is bittersweet. There is something about these characters that Koontz writes, though, that always makes me want to be that better person, that outsider who conquers the sense of inadequacy thrust by society upon those that don’t quite fit. These characters show that the struggle does not have to be futile, and that there is a path – no matter how narrow – for the outsider who lives the better life. I really liked this book and am looking forward to more dark stories like these from Koontz with these types of redeeming characters.